Kim Kardashian unleashed outrage from fans on Instagram last week after sharing some photos with Tesla’s Cybercab and AI-enabled humanoid robot Optimus. In one cute pic, she sits in his angular lap. In another, they hold hands, Optimus’ chrome fingers entwining with Kim’s smooth, manicured ones, tipped with perfect baby-pink nails.

Hail Satan, said one comment. Real footage of how human dehumanise themselfs! wailed another. Kim’s nod to Elon even unleashed speculation about her political views, as one New York Times article reported.

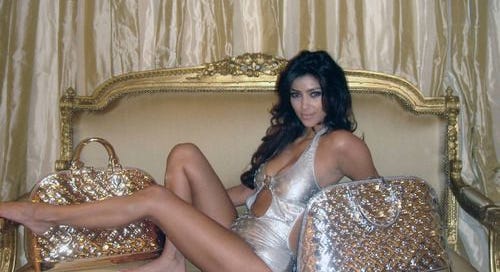

It appears that her followers don’t realize that Kim Kardashian is already a cyborg herself. Her flesh has been modified through an array of technological interventions: her nose and lips sculpted under the fluorescent light of a cosmetic clinic; her waist, fembot-thin, chiseled via the suctioning out of its fatty tissue, then reinserted into her ass to augment it to biology-defying proportions. Her body is a site of technological sublime, an interface between organic matter and technological intervention that yields a new, uncanny aesthetic category. She appears perfect, poreless. Her body seems digitally rendered, even in person. Her beauty explicitly announces itself as a synthetic construction, perfect in its artificiality, yet tantalizingly within reach through technological procedure.

But it’s not just Kardashian’s engagement in bodily modification that speaks of her posthuman detachment from the concept of a fixed self. More radically, she engages in constant fragmentation and multiplication of herself as a pioneer and prophet of a new mode of production—that of the Influencer, which hinges on the performance and commodification of the self through the distribution of one’s digital image. In her status as an influencer—arguably the most successful of all time and the first to perfect the model—she has always been entangled with the forces of technocapital.

Paris Hilton was one of a few “proto-influencers” who began to pioneer the performance-of-self-as-labor in the early to mid-2000s. Beginning with her reality TV show, The Simple Life, Hilton was one of the first to monetize personality rather than talent. With a carefully managed sex tape scandal that leaked in 2004 just after the debut of her show, she was able to generate more buzz, and subsequently leverage her heightened fame into capital through a smattering of department store product lines and fragrance deals. As Hilton’s assistant, Kardashian studied the playbook and took it to the next level.

The Kardashian-Jenner family significantly expanded and systematized the “famous for being famous” model. In 2007, Kim launched her career with a sex tape and a reality TV show, in textbook fashion. Reality TV proved the perfect medium for their ascent—its ambiguous status between fact and fiction created a space in which every gesture, conversation, relationship could be transformed into content. Yet it was their leveraging of social media that proved truly revolutionary. The family systematically expanded their influence across newly emerging platforms—Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, and later TikTok—mastering the distinct logics of digital engagement on each. For the Kardashians, the boundary between life and representation dissolved entirely.

Algorithmically distributed, the Kardashians spawned across platforms, each iteration slightly different, calibrated for its specific digital terrain. Instagram presents one version, TikTok another, Keeping Up With the Kardashians yet another, while magazine covers and billboards boast their own variants. Each of these image-copies becomes a node in the Kardashian Image Complex, an ever-expanding web of representation that constitutes the family’s cultural presence. They exist somewhere between flesh and digital image, spread across multiple platforms and realities, their physical forms merely nodes in an endless circuit of technological reproduction. But even their material bodies, their “real selves”—if they could even be called that—have been constructed specifically to be reproduced. They are hyperreal, copies without an original.

The second breakthrough that turned the Kardashians into Influencer Industrialists was the creation of a sophisticated system that yoked this image-distribution machine to capital accumulation. They built an ecosystem that converts self-performance into content, uses content to attract attention, and transforms attention into capital through their various business ventures. Their reality show, social media presence, and companies operate as a single entity.

The Kardashians were the first to figure out that to accumulate real wealth and power, they had to transition away from licensing deals to creating companies in which they had ownership stakes. Prior to this, it was standard for many “proto-influencers”—including the Kardashians themselves early on in their careers—to do licensing deals for product lines at department stores. The Kardashian-Jenner family took this to the next level, creating an interconnected empire in which each family member could target different demographics through their own companies, all while supporting the whole. This spawned a variety of enterprises, from Kim’s SKIMS shapewear to Kylie Cosmetics to Khloe’s Good American jeans (which have rave reviews), to Kourtney’s Lemme vitamins. Kim even has a private equity firm. The family’s combined net worth is now around $2 billion.

Just as the Kardashian Image Complex distributes itself across a multiplicity of images and platforms, the Kardashian Industrial Complex splinters across multiple vectors of capital—from cosmetics to shapewear to private equity. The family emerges as the first fully-realized prototype of the human-corporation hybrid—a form where the distinction between lived experience and its commodification has ceased to exist altogether.

What’s interesting about Kim—more than any of her sisters or the host of social media influencers who have since adopted the self-performance → capital-accumulation playbook—is her acute awareness of her own posthuman status and her calculated navigation between flesh and simulation. She doesn't merely inhabit this space but actively theorizes it through her own aesthetic choices and marketing strategies. Her consistent deployment of futuristic signifiers—metallic accessories, cyborgian sunglasses, sleek catsuits like second skins, her Cybertruck’s regular social media appearances—performs a knowing engagement with the role of technology in her co-creation.

Earlier this year, in SKIMS’ first national TV commercial, Kim appears in a minimalist, flesh-toned laboratory with an antenna implant protruding from her skull. She oversees multiple clones of herself from a control room lined with video screens, monitoring as robotic arms prod, bounce, and inspect them—explicitly staging the multiplication and manipulation of her image. After the tests complete, she retrieves a printed readout and enters an adjacent room where dozens of Kims stand in various styles of nude shapewear. She hands the slip to one of them as the camera zooms out, revealing they are all in a spaceship, in orbit above the Earth.

Her 2015 book, Selfish, composed entirely of sultry selfies taken on her phone similarly demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of image as performance. These aren't merely branding choices but rather are part of an ongoing metacommentary on contemporary modes of production, in which the self becomes both factory and product. Kim Kardashian embodies a future form of capital accumulation that we're only beginning to understand. She’s self-aware and steps ahead of us all.

Kim Kardashian may be a striking, early example of an emerging paradigm in which capital accrues to those who can perform and commodify themselves best, who can most thoroughly transform themselves into human-technology-market assemblages. Under this new paradigm, technological mediation and market logic cease to be external forces and instead become the very substance of subjectivity. Labor becomes a constant process of self-surveillance and self-commodification that demands total integration with digital systems. Success depends not on what one produces but on who one performs and how well one merges with algorithmic frameworks of visibility. It’s life as performance art as business enterprise. Everyone becomes an influencer.

Good essay.

"These aren't merely branding choices but rather are part of an ongoing metacommentary on contemporary modes of production, in which the self becomes both factory and product."

Can this be done by only a few world-famous people or is it scalable to large numbers of people? Will it be "everybody gets 15 minutes"? Or will it be everybody all the time is both factory and product in countless niches?