The function of the fashion industry, at its core, is to provide options for people to clothe and accessorize their bodies. At its best, clothing is an outward reflection of the inner soul. It provides tools for self-expression and aesthetic experimentation, generates new visual languages, and makes reality cooler, funner, and more interesting.

Providing interesting, thoughtful, creative, high-quality options for people to wear is an important job. But the fashion industry also leverages insecurity and social comparison to drive the Consumption of these Options, often convincing people that the Consumption of the Options is one and the same as the path to fulfillment and self-actualization. (To be fair, this isn’t a failure of the fashion industry alone so much as of the broader consumer capitalist paradigm it operates within, though fashion certainly doesn’t hesitate to indulge that logic.)

The fashion industry also leads people to believe that the Options they Consume—especially the Pricey Options they have access to (said Pricey Options usually being pricey due not to quality nor artfulness, but solely due to their power in broadcasting to others that they are, in fact, the Pricey Option)—make them better than those who do not or cannot Consume such Options.

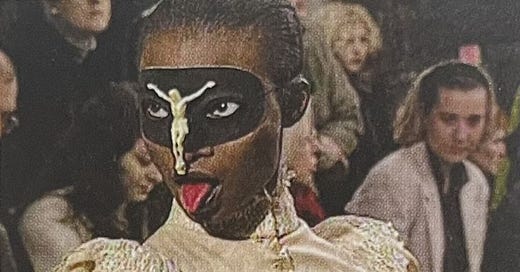

This is because fashion isn’t just about covering the body, it’s about communicating through it. Every article of clothing carries layers of embedded meaning shaped by cultural context. When worn, these meanings are read and interpreted by others, and that interpretation shapes their response—approval, exclusion, suspicion, admiration, indifference. This interaction between clothing, bodies, and social perception forms a symbolic system with its own emergent logic.

As a system, the main functions of fashion are: expressing identity, differentiating people and shaping how they are socially positioned. It’s a language, but instead of words, it uses the clothed body as the medium through which information is transmitted, read, and evaluated. What makes fashion distinct from other symbolic systems is that it is mandatory, embodied, and recursive.

Fashion is mandatory. Pretty much everyone has to wear clothes in pretty much all social contexts. Unlike optional participation in religion or politics, fashion is inescapable. Also, sorry, but believing you don’t engage with fashion doesn’t free you from it. Opting out of fashion norms still sends a message, which may not be readable to you, but is readable to others. Every item you put on your body says something to those who know how to read it. Putting nothing on your body says something too, different things, depending on if you’re at the beach, in the bedroom, or walking down Canal Street in broad daylight.

Fashion assigns meaning to appearance, making the body a key site for the communication of identity and for social evaluation. What one wears can signal, among other things, socioeconomic status, belonging to a social group, cultural literacy, drug use, industry affiliation, affinity for the outdoors, political leaning, religion, sexual orientation, level of security in one’s identity, level of security in one’s body, emotional availability, etc. etc. Because fashion is visual, judgment based on clothing happens more quickly than evaluation based on more complex—and often more important—information about one’s beliefs and values (though the fashion-literate can usually grok this kind of information with some level of accuracy from a person’s clothes alone).

Fashion constantly pulls from its own past—reviving old styles, remixing subcultures, and recycling familiar looks. It is a complex system of multi-layered references. This means that deep participation in the system requires cultural memory and referential fluency more than aesthetic aptitude. What most people get wrong is that fashion isn’t about looking good, it’s about flexing cultural expertise. The most “fashionable” people are often the least legible to the uninitiated.

Because it’s mandatory and embodied, fashion has unusual symbolic power. It can influence how people are interpreted, affect who is granted status or belonging, and alter how individuals are socially positioned without explicit language, institutional authority, or formal rules. You are always “on display,” whether or not you intend to be. You are always evaluated by the appearance of your clothed body, with or without your consent. There is no outside to fashion, only more or less legible positions within the system. There is no off switch. Only outfits.

“fashion is mandatory, embodied, and recursive”.

i totally agree with this.

i think that at its most honest, fashion is a space of expression, a silent language, a visual form of an identity. but in its more toxic form, it becomes a machine of comparison, consumption, and categorization. a constant tension between who we want to be and the fear of never being enough. choosing an identity (as fashion often seems to ask us to do) it can feel exciting at first, like discovering a new version of yourself, but when that identity stops feeling true, changing becomes more difficult. because you don’t just let go of clothes or a look but you let go of who you thought you were.

reading this also made me wonder of this: what does it mean to choose an identity in a system that’s constantly offering us new ones to perform and consume? sincerely, sometimes i feel like the very act of choosing becomes performative—and other times, i’m not even sure whether i’m choosing freely.

“you have to wear clothes most of the time and the clothes you wear send a message to other people” thank you for this brilliant analysis that can be summed up to a single sentence we all already implicitly understand. Looks you can’t opt in to good writing, either. Sorry :(